AI, Truth-telling, and the Return of the Eyewitness Account

"Were you there? What did you see? Can I trust you?" will be the questions we wrestle with in the AI age

I’ve been reading a lot of articles and listening to a lot of podcasts about artificial intelligence. Here are a few of them:

And this one I’m going to watch in full soon:

Even the new pope is talking about AI, as Dr. Steven Umbrello writes in Word on Fire,

By taking the name Leo, the new pope signaled that the Church would face today’s transformative technological upheaval with similar courage and clarity. In his early remarks, Pope Leo XIV identified artificial intelligence (AI) as a central social and moral challenge of his papacy—a “new social question” requiring the Church’s wisdom both ancient and new. Echoing his namesake, he positioned his pontificate to address the rerum novarum (“new things”) of our age in continuity with the Church’s tradition.

It’s a lot to take in. If you have not been using chatGPT or Grok or one of the other AI systems, it would be easy at this point to not really understand why people are getting so concerned. You go about your day and do your job and spend time with your family, and there is no AI in sight. But if you have started using these systems for daily tasks, you can sense both their power and their danger.

As a pastor, I have begun using Grok or ChatGPT mostly to help me with sermon research and preparation. It is genuinely helpful in finding quotes, summarizing research on topics, and I also sometimes have it make an outline from my written manuscript. This has helped me trim down my sermons and organize my thoughts. I have been amazed and at times troubled by just how intelligent it seems, and how much better these systems seem to be getting by the week.

This is especially true in their image and video production capabilities. Watch this video of Google’s VEO 3 video generation. It’s unreal:

If AI’s ability to create realistic images and videos improves at the rate it has been (and right now that rate feels exponential), we are looking at probably a year or two, maybe earlier, until there will be no way to verify if a video or image is real or AI-generated.

This, of course, has tons of implications for those in the creative world of photography, visual arts, graphic design, and filmmaking. My son has said he wants to be an artist when he grows up; pre-AI, that was a always a tough field to make a living in. But will it be a field at all in a few decades? It’s pretty hard to see how.

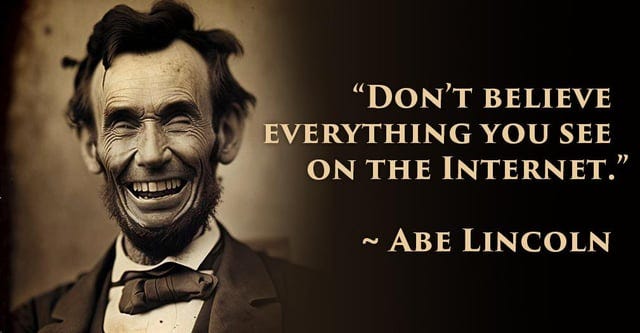

But my curiosity today is what AI-generated images and video will mean for our ability as humans to assess truth. We’ve learned in the past two decades to be somewhat skeptical of the claims made on the Internet, but will we soon have any ability to verify what’s true from what’s false?

And if we do arrive at that point, then what are our options? How will we move forward as a society if we can no longer rely on what we once though of as unbiased witnesses, the camera and then the video camera? How will we know, for instance, if that really is the president speaking on that video on X, or if that city really has been rioting, or if that foreign capital really is being bombed by its enemies? How will we know if the voice on our phone actually is our mother asking for help? How will banks determine their real clients from digital pirate avatars? How will we determine if an author actually wrote their book, or if an actor really recited their lines? How will the judge weigh evidence? Was that security footage altered by an AI to protect the defendant, or is he really innocent? Was that voice recording in a police sting real or was it fabricated? How will teachers examine their students or have them write papers? How will they ever determine what is student-generated and what is AI-generated work?

These will all, in a matter of years if not months, be very live questions for us to figure out.

I believe that the arts, journalism, education, and the justice system are the four most important places where AI will cause a massive change, not just in basic day-to-day practice, but in our fundamental understanding of how we assess truth. And though AI companies and advocates push the technologies as a way to leap forward (and certainly in many respects they are right), I believe that in these three realms AI will push us backward, toward a pre-technological view of truth-telling, meaning to what truth-telling was like before the common use of cameras and video cameras.

Here is my basic thinking:

If we cannot distinguish true images and videos from AI-generated ones, we will have to dismiss all images and videos as sources of truth.

Apart from images and videos, all we have left in truth assessment is the eyewitness account.

Truth-telling, therefore, on a human level, will return to pre-technological standards and practices.

AI will usher in a new age of the eyewitness account

This is what I’m imagining. Before video and photography, there was basically one way to tell that something happened: there was an eyewitness, and that eyewitness told his account. The truth of the event, therefore, was rooted in the trust one had in the human eyewitness. Think of the soldier in the Civil War. He participates in a battle; he writes down what happens in a letter; he sends it to his loved ones. They believe that the battle happened in such a way because they trust the eyewitness.

This is how newspapers functioned for many years, too. There was an important event. And there were many people from regional and local newspapers, human beings called reporters, who went there and either saw the event or talked to people who saw it. They wrote a story, to the best of their ability, on what happened, based on eyewitness accounts. And then, the readers of that paper, trusting in that journalistic process, believed that the event the story described actually happened. Why? Because they trusted the reporter and his or her commitment to truth-telling.

This all may seem like a very obvious thing to spell out, but it’s really not. We now very rarely have this same kind of commitment to an eyewitness account, because we trust in videos and images. Very few newspapers have the money to send out reporters to the places where events are happening. They rely on one video, one image, and a few phone calls—but rarely was one of their own reporters actually there.

Recently, journalist Douglass Murray had a debate with comedian Dave Smith on the the Joe Rogan podcast; much of it had to do with the war in Gaza, but on a larger level it had to do with the need for experts in order to discern truth, even though we have often been let down by experts. Douglass Murray was stunned that Dave Smith, who talks a lot about the Israel/Palestine conflict, has never been there. He’s never seen it for himself and come back to report. Smith found this condescending, but for Murray, this is just basic part of journalistic integrity. Actually seeing what you are talking about.

I believe that in the age of AI, we will all expect just what Murray here thinks is necessary: a human eyewitness account.

I think that AI will help us rediscover what has been true all along, that discerning truth is inescapably tied to trusting in other human beings. Undoubtedly, this will also mean that lying will have much larger consequences socially. If you lie, as in ages past, you will be dismissed from society. The old proverb, your word is your bond, will become palpably true for the ordinary person as well as for the reporter, and we pray that it will be true also for the politician. I think we are seeing the beginning of this in the wholesale rejection of what was once called the mainstream media, which by the numbers should not be called mainstream anymore. If you are in the business of truth-telling, and you are for years caught in blatant lies, at some point the audience walks away.

Conclusion: AI is scary, and yet might be good for our understanding of truth

This is the strange thing, I think. For about a hundred years or more, we have been able to use photos and videos to verify events, and because of this we’ve not had to rely on eyewitness accounts as much (which, of course, are often flawed or downright false). This brought us a false impression that we could ascertain what really happened without having to rely on a human being being trustworthy. We believed that we could get to the real or the actual without having to deal with that annoying problem, the human being. But AI now is pushing us back into the past, back into a reliance on one another.

Were you there? What did you see? Can I trust you?

These will be the questions we must wrestle with in the days to come.

Of course, for Christians, we have staked our life on the trustworthiness of eyewitness accounts. Men like Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, and Paul, all who saw with their own eyes or who interviewed people who saw with their own eyes, the one who they believed was the son of God. There is no video, no image, nothing but our trust, our faith, rather, that these eyewitnesses were telling the truth.

John here writes in his first letter:

That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked at and our hands have touched—this we proclaim concerning the Word of life. The life appeared; we have seen it and testify to it, and we proclaim to you the eternal life, which was with the Father and has appeared to us. We proclaim to you what we have seen and heard, so that you also may have fellowship with us. And our fellowship is with the Father and with his Son, Jesus Christ.

-1 John 1:1-3

AI is a very scary technology, and it’s so powerful that it’s almost impossible to predict what is coming. I do not what to live in a world where art and poetry and movies and music are made by robots. It’s hard to think of anything worse, actually, and I generally think that Christians should resist the world that AI seems to create with all of who we are.

But. If it makes us all Internet-skeptics, cautious to believe the first image we see, if AI leads us to need more human connection and less digital interface, it it calls us to rely more upon one another, upon bearing true witness to the events of our lives, to trust more in the ability of humans not only to witness the truth but to report it, then I think AI could bring at least some good to this world. But man. What a different world will it be.

Supporting Wright Writes

If you are enjoying the work of this Substack and would like to support me, please consider:

Subscribing to receive future posts on Tuesdays and Fridays (it’s free to do so!)

Sharing an article on social media or with a friend (this really helps)

Buying me a coffee by the link below

Upgrading to a paid subscription